What was life like as a ground attack pilot on the other side of the Iron Curtain, flying the challenging MiG-23BN attack aircraft with East Germany’s air arm? Some of the tactics may have been familiar in the West, but certain underlying doctrines weren’t

After being founded on 1 March 1956, the air force of the German Democratic Republic’s National People’s Army — the Nationale Volksarmee, or NVA — developed into an efficient and powerful entity. When considered alongside the Soviet 16th Air Army, stationed in the GDR as part of the Group of Soviet Armed Forces in Germany, it made up a huge combat force on the border with NATO’s armed forces.

In the event of a ‘hot’ conflict in Europe, its role would have become offensive, implementing both conventional and nuclear capabilities, and using tactical atomic bombs. Although the GDR’s Luftstreitkräfte, or LSK, had the most modern Soviet weapon systems in its inventory, it possessed no heavy bombers, and thus no strategic role.

“Certain combat manoeuvres in the MiG-23BN were hazardous

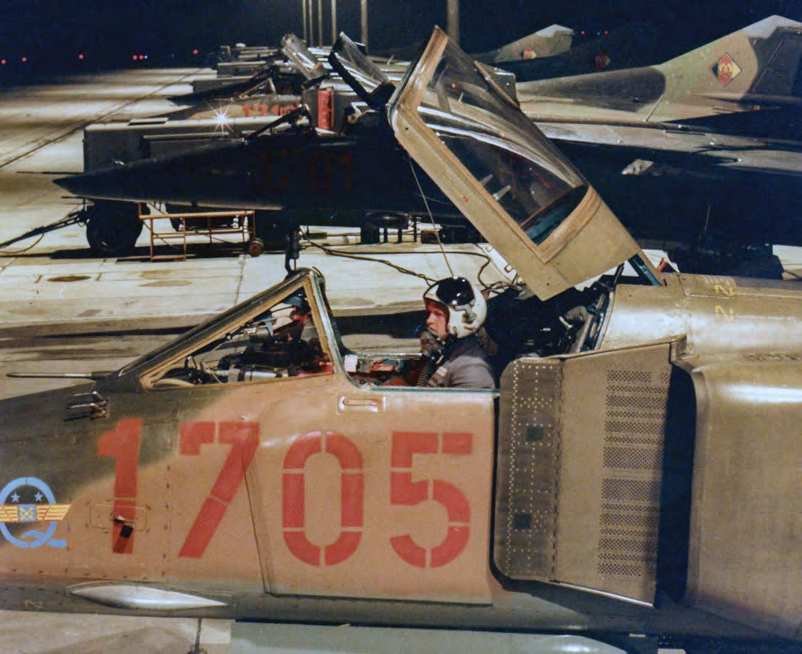

Andreas Dietrich began his service in the LSK on 15 August 1977 as an officer student. A year later he learned he was one of 30 young men selected to undertake a full military pilot course in the USSR. They would be trained on the ultra-modern MiG-23MF, NATO codename ‘Flogger-B’. The four-year course at several Soviet colleges and flying training schools began in 1979, and concluded in September 1983 with a state examination. Assigned that November to LSK unit Jagdbombergeschwader 37 at Drewitz, together with 10 other MiG-23MF graduates, Andreas started conversion training on the MiG-23BN fighter-bomber.

“We 11 young pilots got to know all the technical systems of the MiG-23BN in a three-month theory course”, he recalls. “In particular, the flight controls, the navigation system and the weapons system, which were somewhat different from the MiG-23MF, were real challenges. In April 1984 we were ready for our first flights on type.

“Today I can say the transition went smoothly. Only the specifics of landing caused some problems at first. We had to learn to land the BN carefully and precisely. Later we had that under control and landed the BN without any problems, even in the most difficult weather with crosswinds, and also at night. However, especially in the landing phase, the MiG-23BN remained dangerous and reacted directly to inaccurate parameters or negligent handling.”

The MiG-23BN was considered to be the most difficult combat aircraft to fly in the Warsaw Pact countries. It was an efficient ground attack platform, the role it was designed for, while its stability and low-level target acquisition were also good. But certain complex combat manoeuvres could be hazardous. Because the autopilot was directly coupled to the inertial navigation platform — which in turn did not allow any abrupt manoeuvres or even aerobatics — the risk of failure of the attitude control system or one of the two main display devices, the compass and the artificial horizon, was constant. Manoeuvres such as looping or rolling were therefore prohibited in the BN.

The LSK’s MiG-23BNs were equipped with the latest upgrades and were identical to those delivered to the Soviet Air Force. This was not always the case with the Warsaw Pact countries, which sometimes received ‘special’ export models. For example, the East German BNs had two hydraulic actuators in the rudder channel, which prevented a yaw moment from developing around the vertical axis at high angles of attack, and thus asymmetric airflow into the engine with the risk of a transition into a shallow spin. The three ‘Flogger-H’ losses suffered by JBG-37 can be traced directly to angle of attack problems. Dietrich says, “Their pilots apparently did not notice the perceptible signs before the transition into a spin at angles of attack greater than 18°, and the BN may have continued to fly erratically and to descend.

“I myself found the peculiar inertia of the BN to be pleasant, because it allowed the flight parameters to be adhered to fairly well… Having available information on the distance to a programmed point or destination airfield was ingenious and indispensable. The MiG-23BN also had a device that is still not a matter of course in combat aircraft today. It had an SAU-23B autopilot, which allowed the aeroplane to fly fully automatically en route, all the way to landing. The pilot just had to regulate the speed accordingly.

“Since the development of onboard electronics had not yet come up with laser-based gyroscopes or purely electronic microswitches, the computing power of the autopilot was relatively low, and therefore its reactions to sensitive course corrections — especially in the final phase of the landing approach — were rather sluggish. I therefore only did fully automated approaches when it was necessary to check the on-board system on technical check flights and to release it for general flight operations. Otherwise, I always preferred to use the command control that is available in almost every modern cockpit today, which uses small bars to indicate horizontal and vertical deviation from the ideal glidepath. At the same time, small command pointers indicated in which direction the stick should be moved in order to return to the ideal glidepath or course.”

The missions JBG-37 performed with its MiG-23BNs were dedicated to the protection and defence of the GDR. All tactical training and deployment planning reflected this. The LSK’s two fighter-bomber squadrons, JBG-37 and JBG-77 — as well as the two Sukhoi Su-22M4 ‘Fitter’ squadrons that formed part of Marinefliegergeschwader 28 within the naval forces — were, in the mid-1980s, prepared for offensive operations against NATO in the event of a conflict in central Europe. Had war broken out, JBG-37 would have been fully integrated into the Soviet 16th Air Army and fulfilled the tactical tasks assigned by it. Primarily, these would have been conventional strikes against important NATO military ground targets such as airfields, armour and tactical missiles. The use of small-calibre tactical nuclear bombs against strategically important objectives was planned as a secondary mission.

Compared to today’s advanced weapon systems, the MiG-23BN was a relatively simple machine. All armament functions were selected manually by the pilot; among other things, there was a bulky weapon selector switch below the central instrument panel, which had to be turned by hand. The training of combat manoeuvres and the use of weapons was strictly bound to the relevant East German regulations and left no room for individual variations or interpretations. All pilots flew the same manoeuvres within the same parameters according to the same tactical guidelines. There was no real pilot autonomy whatsoever.

“The GSh-23L cannon was incredibly easy to operate”, says Dietrich. “For this the weapon selector switch had to be set to ‘cannon’. Only two more switches had to be operated and it was ready for use. For sighting ground targets, the laser range-finder mounted in the nose calculated the distance to the point of impact of the projectiles. This information was processed in the weapon computer, together with other flight parameters such as the air speed, ground speed, altitude, angle of bank and so on, and was displayed as the exact position of the target cross on the head-up display. A green light on the sight and a beep in the headphones signalled that the effective distance had been reached and firing could begin.

ANATOMY OF THE ‘FLOGGER-H’

The MiG-23BN, or ‘Flogger-H’, was a development of the MiG-23B, the ‘Flogger-F’.In the mid-1960s, the Soviet Union recognised the need for a new attack aircraft, and initiated the MiG-27Sh project to meet this requirement. However, it was abandoned in 1969. Instead it was decided to base the new aircraft on the MiG-23 design, which already existed in the form of the MiG-23S, NATO codename ‘Flogger-A’. Flight tests began on 23 May 1969. The most visible change was the completely redesigned nose, which contained such as the PrNK-23S SN navigation attack system and its laser range-finder, an analogue computer and the PBK-3 bomb sight. The engine was the Lyulka AL-21F-3, which — at 17,175lb dry thrust and 24,684lb with afterburner — was more powerful than the R-27F2-300 of the MiG-23S.

The twin-barrel 23mm Gryazev-Shipunov GSh-23L cannon was mounted in the fuselage. Of seven external weapon stations, two were located under each immovable portion of the variable-geometry wing and two more under each of the pair of air inlet ducts. The fifth station was beneath the fuselage, used exclusively for an 800-litre auxiliary fuel tank. Under both sides of the rear fuselage were a final two stations for smaller bombs. Overall, the MiG-23B could carry a weapon load of three tons.

Only a limited number of MiG-23Bs were built, as the variant was soon superseded by the MiG-23BN. Fundamental differences between the ‘Flogger-F’ and ‘Flogger-H’ started with the wings, which were given an increased area, extendable leading edges and a distinctive saw-tooth design. The navigation system was updated to the PrNK-23N. Due to high demand for the Lyulka engine for use in the Sukhoi Su-17 and Su-22, the decision was made to use the Tumansky R-29-300, with certain modifications. Dry thrust was 17,310lb, rising to 24,728lb in afterburner.

The BN’s external loads included a maximum of four lots of 32 unguided S-5 rockets in either UB-16 or UB-32 pods, 20 unguided S-8 rockets in two B-8M1 launch containers, four S-24 unguided missiles, one or two Kh-23 guided air-to-surface missiles, a maximum of three tons of FAB-100, FAB-250 or FAB-500 bombs, and a single RN-24, RN-28 or RN-40 tactical nuclear bomb of varying explosive power.

“At the same time, the diminishing distance to the target was displayed on the HUD by an ever-smaller quarter-circle. Firing had to cease when a red light on the sight came on and the effective range on the HUD had expired. It must also be mentioned that the double-barrelled cannon was an absolutely reliable, high-tech product of Soviet military technology. At around 50kg, it was lightweight and fired 23mm bullets at a rate of 50 rounds per second. To save ammunition, the rate of fire could be limited to 18 rounds per second using an additional switch.”

A typical armament variation for the MiG-23BN was four UB-16 or UB-32 rocket pods, which could take 64 or 128 unguided S-5 rockets. When training, however, usually only four to six were held in two UB-16 pods. Alternatively, one or two 50kg concrete bombs were dropped during free-fall bomb training. Flights involving active use of the Kh-23 guided air-to-surface missile were carried out very rarely, during larger tactical exercises and always limited to a few select pilots. Obviously, budgetary factors played an important role here, and the same limitation applied to the use of heavier bombs.

The manual firing of unguided rockets and the dropping of ‘dumb’ bombs was not very accurate, and it was considered likely that at least two aircraft would have had to go in against a target during an actual war. “The destruction of a target could only be guaranteed through the paired or grouped use of the MiG-23BN”, says Dietrich. “Because the identification of ground targets was done visually and the aircraft manoeuvred relatively little, the MiG-23BN would have been very vulnerable there. Leaving the target area would always have brought a high risk of loss. Any capable means of defence would have taken the BN out of the sky, as it would not have been able to perform abrupt evasive manoeuvres at high air speeds, and due to its relative inertia near the ground. In addition, our BNs were unable to launch infra-red decoys against anti-aircraft missiles. In my view, this forced the pilots to operate under time pressure, making a single attack at a high air speed in the target area.”

The possible use of nuclear weapons by the NVA was very strictly regulated, monitored and controlled by the Soviet military leadership. The tactical nuclear bomb that would have been used by JBG-37’s MiG-23BNs was either the RN-24 or, more likely, the RN-28. The explosive power of the latter could be varied: 1kT, 5.3kT or 10kT. With retardation, it detonated at heights of zero to 250m. The bombs themselves were stored under close guard at Brand, the base of the Soviet 116th Fighter-Bomber Aviation Regiment.

Andreas explains, “We pilots practised the combat manoeuvre for the use of the nuclear bomb solely at Drewitz, the only base for the MiG-23BNs of the NVA air force. This was a compulsory part of our pilot qualification. The manoeuvre resembled a very large traffic pattern, limited by two 180° curves. After the second 180° turn, the aircraft ended up on the so-called combat course — the flight path in a straight line to the target. Here the pilot brought the BN to a speed of 900km/h and an altitude of 100m.

“The peculiarity was that 12km from the target, control was passed to the autopilot. From this point on, it flew the aircraft fully automatically to the target area and, also fully automatically, initiated the climb manoeuvre based on the climb angle calculated by the weapons computer and the navigation system. The symbolic release of the free-fall nuclear bomb was just as fully automatic, symbolic because we didn’t actually have a bomb on board. Now the voice information system informed the pilot to take control of the aircraft again. That instant was the only critical moment during the entire manoeuvre, but it was not a problem for the experienced pilot.

“Nevertheless, in 1985 a pilot on our squadron died during this manoeuvre. Unexpectedly, he flew into cloud cover at an altitude of 1,500m and lost spatial orientation. Probably in a panic, he banked the MiG-23BN over, and it fell into a flat spin. I saw how the aeroplane came out of the clouds and exploded seconds later in a forest. The pilot was not able to eject.”

During the 1980s, JBG-37 took part in various exercises with its MiG-23BNs, up to nine a year. They included training with ground troops in the close air support role, manoeuvres with naval forces including real and simulated attacks on sea targets, and exercises with other Warsaw Pact armed forces. The electronic countermeasures of ground-based air defence systems were tested by the BN’s SPS-141 jamming system. On occasion, pilots were afforded the opportunity to use weapons against ‘real’ targets, like the launching of unguided, largecalibre S-24 missiles at wartime Kriegsmarine destroyers, some of which were filled with concrete and grounded off the Baltic coast north of Peenemünde.

Dietrich recalls, “It was always a highlight to be able to fire a complete set of unguided S-5 rockets from four UB-32 pods, and much-requested. A MiG-23BN then could fire 128 unguided rockets at a ground target within four seconds. Regardless of the fact that you had to aim precisely and that the cockpit smelled of powder, the effect on the target looked devastating on film and in photos. I remember that during a troop exercise on a large firing range near Magdeburg, several of our aircraft each dropped six 250kg bombs to clear the way past an obstruction in the water. It must have looked very impressive, at least from the ground.

“However, it was always a special event when we were able to deploy the Kh-23 guided missile. For this purpose we had a special simulator to practise the somewhat strange control of the guided weapon with the multidirectional switch attached to the BN’s control stick. Due to the sluggish signal transmission to the rocket, its control was somewhat critical despite the clearly visible optical aid, a white torch in the rear of the rocket. Once, two missiles of this type made themselves ‘independent’ during an exercise and did not fly towards the target. After this, practice Kh-23 launches took place only exceptionally, in the interests of minimising collateral damage.”

Although the MiG-23BN was not designed as an interceptor, and taking into account its limitations, it was recognised that there might be opportunities to combat aerial threats. For this purpose, JBG-37 rehearsed the necessary procedures. In Exercise ‘Granit ’86’, Soviet Tupolev Tu-22 bombers approaching the training area were the target.

Maj Heinz-Hermann Gaedke recalls, “For the interception of aerial targets, pilots from JBG-37 with two MiG-23BNs were assigned to the duty system [DHS, equivalent to NATO’s quick reaction alert] of Jagdfliegergeschwader 8 [a MiG-21 unit]. Perhaps half an hour later the DHS alarm came. After take-off, we flew to a holding area and were then guided east to the Tu-22s by ground control… However, the Tu-22s were very fast. I think they were flying at Mach 0.98 at a very high altitude. We had to engage the afterburner to get into an attack position, because at such speeds and altitudes, interception would not have been possible without it.

“The use of nuclear weapons was controlled by the Soviets ”

“We had to intercept six machines. Each time we would approach, fly a curved firing pass, leave the attack and then start a new one. We had no gun cameras in the MiG-23BN, so the intercepts were evaluated via the flight parameters recorded on the flight data recorder and the length of time the combat button was pressed. My wingman and I ended up with the bare minimum quantity of fuel allowable, but we had fulfilled the supporting role of air defence by fighter-bombers.”

There were regular exchanges with other Warsaw Pact flying units, too. From 1987-89, one was held with the 28. Stíhací Bombardovací Letecký Pluk (Fighter-Bomber Air Regiment) of the Czechoslovak Air Force based at Cáslav, which also flew the MiG-23BN, while between 9 and 11 April 1989 a joint exercise with the 559th Fighter-Bomber Regiment of the Soviet Air Force, equipped with the MiG-27K, took place at Finsterwalde.

A larger series of manoeuvres was held from 9-16 September 1989, when MiG-23BNs from JBG-37 and Su-22s belonging to JBG-77 and MFG-28, both based at Laage, flew to Luninets in Belarus for a tactical exercise. They were accompanied by senior LSK staff officers, who arrived in a Tu-134 belonging to Transportfliegergeschwader 44.

Luninets and the adjacent Kolki range provided an important training facility for the air forces of the Soviet Union and its allies. The aim was to instruct pilots in the location, acquisition and destruction of ground targets using guided missiles, rockets, on-board cannon and bombs. The missions for JBG-37’s four pilots began on the second day of their deployment. For one of them, Maj Wolfgang Kuhnert, it was a very important occasion.

“The task assigned to me was to steer a Kh-23 guided missile [NATO designation AS-7 ‘Kerry’] into the target with the least possible deviation”, he recalls. “I still needed to perform two rocket launches before I could qualify as a ‘master pilot’. In particular, the chance to use our armament in practical combat manoeuvres and under warlike conditions at Luninets made this tactical exercise particularly valuable.

“I flew two Kh-23 sorties that day. The first was a training flight with a simulated missile attack. After landing back, the aircraft was prepared for a live launch. The engineer had meanwhile written ‘Greetings from the GDR’ in colour on the rocket in Russian. The take-off and the approach to the target area went smoothly. In the target area I flew the attack manoeuvre we’d trained for and sent the appropriate commands via radio. I could easily identify the ground target assigned to me. Then everything went very quickly. I reported ‘Start’ and pressed the button on the control stick. In an instant, the huge, white missile with a trail of white smoke whizzed past me to the left. From now on I spoke loudly to myself, constantly shouting the missile control commands: ‘Up… up… left… down… up a little…’

“The Kh-23 was a remote-controlled rocket that worked according to the following principle: the pilot’s eye, the bright torch in the rear of the rocket and the target must always be in line. But there was a special feature: press the multi-directional button on the control stick — the rocket climbed. Push the button up quickly — the rocket climbed quickly. The pilot therefore had to control the rocket very precisely, otherwise he had not the slightest chance of getting it to the target. In the event, the Kh-23 I fired made it to the intended point of impact. The ground target, a hardened aircraft shelter, was hit… the large amount of explosives carried by the Kh-23 detonated and it was destroyed.

“According to the safety regulations, it was mandatory to fly a vigorous evasive manoeuvre immediately after the impact and detonation in order to get out of the fragmentation zone. I delayed this manoeuvre by a split second to see the result of the hit for myself. When I saw that the target was shrouded in smoke, I knew that it was definitely a hit, and therefore would mean at least a ‘good’ rating. All my pent-up emotions were discharged in a comment that was a little too loud over the radio, which immediately saw me being given a warning: ‘Keep radio discipline!’” In fact, Kuhnert received a ‘very good’ rating for his attack.

The following day, the MiG-23BNs were selected to strike an airfield on which wooden dummies of NATO aircraft had been set up. Each MiG was given specific targets to destroy. The target area was approached in finger-four formation. Air defence surface-to-air missile systems were located along the route, and the four BNs had to neutralise their threat using the SPS-141 system. The attack was to take place at an extremely low altitude, and they were only allowed to remain in the target area for a maximum of 30 seconds. The approach to the target also involved evasive manoeuvres to try and fox the air defences, involving rapid course changes with equally quick changes in altitude. Holding formation was difficult.

Kuhnert continues, “At exactly 13.50hrs, our 250kg bombs hit the eastern side of the runway of the airfield we were attacking. Since the attack was carried out from extremely low altitude at high speed, we were going fast enough after the bombing run to escape our own fragments, to fly evasive manoeuvres against the air defences, to switch the weapon system to ‘cannon’ and to carry out the next attack. All manoeuvres were flown with high bank angles at up to 1,000km/h and under large g-loadings. Our aeroplane held formation as if nailed to a board. This enabled us, as planned, to attack the enemy’s [QRA] facilities as the next target with all four GSh-23L on-board cannon. The effect of the 23mm shells was devastating. After the attack, only fragments of the wooden decoys were left.”

Another sortie took place late that afternoon, the target area again being hit by the four MiGs using bombs and cannon with equal success. In the evening, preparations were made for Kuhnert to fly a night mission and fire a Kh-23 rocket at a ground target, making him the first LSK pilot to do so. He got airborne punctually and arrived over the target at the specified time. Once more the objective was a HAS at the south-eastern end of the runway. Kuhnert pressed the launch button.

“It was necessary to fly an evasive manoeuvre after a Kh-23 strike ”

“A split second later, a bright ball of fire hissed past my cockpit. The regulations for night use of the Kh-23 recommended that the pilot should not look into the bright light of the rocket engine. Those who could not resist this temptation had little chance of controlling the missile due to the strong glare. After the rocket had been on the move for a few seconds, I began to say the control commands out loud again. Just like during the daytime flight, the missile hit the target. The detonation and the associated fireball were enormous…”

After their time at Luninets, the JBG-37 pilots and technicians had every reason to be proud of their achievements, in particular Kuhnert, who had finally attained his master pilot qualification. But soon political events brought a time of change for the whole of the NVA. The peaceful revolution in the GDR and the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 signalled the end of Erich Honecker’s government. On 18 March 1990, the country’s first free elections took place, and German reunification was very much on the agenda.

JBG-37’s last flights took place on 25 September 1990. Following reunification on 3 October, the NVA ceased to exist, and the unit was disbanded on 12 December. All its aircraft and associated equipment were brought together in storage facilities and deactivated. The official conclusion was couched in formal East German terminology. It read, “All the tasks assigned to JBG-37 in the interest of defending the national borders and the country were always carried out in full and with great motivation by the military.”